By Matthew M. Thomas

I was excited to recently learn of a great project to excavate, reconstruct, and reuse an open-air stone and earth boiling arch for supporting a flat pan for boiling maple sap.

With the help of the Boy Scouts from Erie County’s General McLane School District Troop 176 and Legacy Troop 73, Boy Scout J.C. Williams completed this project as part of his Eagle Badge at the sugarbush of the Hurry Hill Maple Farm and Museum near Edinboro, Pennsylvania.

Hurry Hill Maple Farm and Museum is home to a great family-friendly maple museum that showcases the history of maple syrup but also tells the tale of the back story of Virginia Sorensen’s 1957 Newberry Award winning children’s book, Miracles on Maple Hill. In writing the book, Virginia Sorensen drew from her experiences living in northwest Pennsylvania. A significant portion of the story of Miracles on Maple Hill centers on activities in a rural sugarhouse and sugarbush as a family struggles to work together to overcome and deal with the father’s trauma of returning to home life after World War Two.

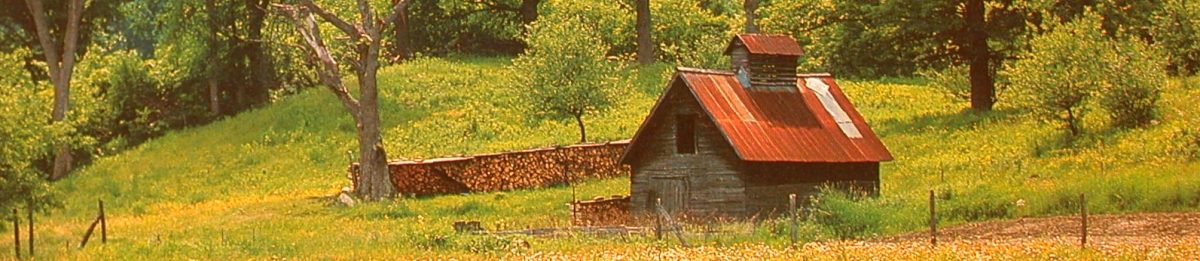

But Hurry Hill Maple Farm and Museum is much more than a museum, which is open all year round. Hurry Hill also has a working sugarbush and outdoor maple history interpretive walking trail that are open for visitors during the sugaring season. The methods and appearance of the syrup making in the sugarhouse are fairly rustic and consistent with what one would see in much of the 20th century. In fact, construction of two sugarhouses on the farm date to 1930. Also on display are a series of large iron kettles suspended over an open fire to show how maple sugaring was done in the colonial era.

On the annual Northwest Pennsylvania Maple Association Taste & Tour weekend, Scouts from the above-mentioned troops are busy demonstrating boiling sap in the iron kettles, explaining the history and process to interested visitors. It is common at demonstration sites teaching about the history of maple syrup to show the colonial era method of boiling in kettles. Luckily for the Scouts, who otherwise spend the weekend standing around in the cold and wind, they have protection from the elements in the form of an Adirondack shelter that was built at the site in 2013 as part of another Scout’s Eagle Badge project.

What was is usually missing from the presentation of the evolution of sap boiling technology is the use of a flat pan on a rudimentary platform and firebox, a boiling method that replaced the less efficient kettles but preceded the shift to formal commercial evaporators and the construction of sugar houses.

Thankfully, Hurry Hill Maple Farm’s owner Janet Woods, whose family has been working this sugarbush since 1939, realized that there was the long-forgotten remains of an old stone and earth arch perfectly situated in the sugarbush along the interpretive walking trail between the sugarhouse, the kettles and Adirondack shelter. From his previous years of telling about the kettle boiling process at the Taste & Tour weekend, senior scout J.C. Williams had an understanding of the role of the arch and flat pan in the evolution of boiling technology. Through conversations with Janet Woods, J.C. Williams was also aware of the presence of the remains of the old stone and earth arch and proposed that as his Eagle Badge project, the Scout Troop would dig it up and rebuild it in the fall and in the following spring use it to boil sap with a flat pan.

Plans were put into motion and the excavation and reconstruction work was caried out over the course of a weekend in October 2022, under the direction of J. C. Williams and with the assistance of a few of his fellow scouts, their fathers, and the troop leader Eric Marendt. Initially, measurements and notes were made of the size, shape and appearance to be able to rebuild the arch as close to those specifications as possible. After that, vegetation was cleared and the soil was removed from around the rocks and in the central firebox area.

Having visited Hurry Hill Maple Farm and Museum the previous summer, Janet Woods was aware of my interest in all things maple history but she also knew that I was an archaeologist who actually had first-hand experience with researching and documenting stone and earth boiling arches. Janet contacted me to tell me about their progress and ask for any advice or details of what to look for and expect. I spoke briefly with the scouts on the day of the excavation to give them an idea of what their digging might find. I also sent them a handful of historic photos of similar arches in use as well as some images from archaeological investigations of arches.

I also shared that from my research experience and from my knowledge of other excavations of similar arches, it was very common to find miscellaneous pieces of old heavy metal that were used as makeshift fire grates, supports and leveling pieces for the flat pan, and as walls to the interior fire ox and arch door. True to form, the scout’s excavation work uncovered an assortment of metal from old car parts, metal bar, and an old cross-cut saw blade.

After dismantling the arch, the scouts rebuilt it with an eye to making it a strong, functional and level support for a heavy metal flat pan that would be filled with maple sap for boiling the following spring. Repurposed old pieces of metal pipe and a grate were added for the fire box and as supports to slide the 3 1/2 foot by 4 /1/2 foot flat pan on and off the fire.

As an archaeologist I have had the priveledge of finding and recording dozens of similar stone arches and have read reports of similar investigations of abandoned arches, some bult for small 2 x 3 flat pans and other built for pans possibly as large as 5 x 12 feet.

In the case of this project, it was especially enjoyable for me to see that not only were these scouts able to learn something about arch technology and use from its excavation, but in the spirit of experimental archaeology, that they were going to learn even more by taking it to the next two steps of rebuilding and reusing the arch. It is true that there are still many backyard sugarmakers that use a small flat pan like was used here, but most folks build cinderblock arches or use some other modern materials.

It is exceedingly rare today to find anyone still building a stone and earth arch. With the help of a knowledgeable volunteer at Hurry Hill Maple Farm, the scouts had a bonus of a geology lesson, when Kirk Johnson, himself an Eagle Scout 55 years ago, explained the glacial significance and thermal properties of the large glacial erratic granite boulders that had been selected and used in the original build of the arch.

Like the many hundreds and thousands of families that constructed arches their sugarbushes from the stones and left over metal at their disposal, these scouts had the real experience of learning how to best, level the pan and boil in a stone arch, not to mention how to get the best fire and airflow. If one thing is true, scouts love a reason to play with fire and you can bet that by the end of the weekend, these scouts had a pretty strong boil going from the 50 gallons they collected from pails on nearby trees.

With the arrival of the 2023 maple season and the annual Taste & Tour weekend at Hurry Hill Maple Farm, the scouts were able to put their work to the test and add the reconstructed stone arch and flat pan to the maple history tour and educational program. In mid-March, six scouts camped out in the snow along side the Adirondack shelter, kettles, and flat pan with additional scouts from the troop joining during the day to help with the tour, keeping the fires burning and the steam rising.

Many maple education programs suffer from an over-emphasis on romanticized presentations of the early history of maple syrup and sugar making technology, such as showing the use of kettles but leaving out flat pans. In fact, one could argue that the use of flat pans and stone arches like the one rebuilt at Hurry Hill Maple Farm was even more extensive in numbers and spread and had a much greater economic importance than the era and use of iron kettles. As a promoter and sometimes critic of the telling of maple history, what made me happy with this story, besides simply seeing a younger generation show interest in maple syrup history, was that Hurry Hill Maple Farm was now able to tell and show visitors a more complete history of the changes and improvements to maple syrup technology. What was a great maple history museum and very good maple education program is only that much better.

Special thanks to Janet Woods, Eric Marendt, and the scouts from Troops 73 and 176 for sharing their story and photos of this project and letting us all enjoy this experience.