By Matthew M. Thomas

This post continues the story of the fictitious John Shelby, the Maple Sugar Man of Barre, Vermont. Part One of the story, focusing in the events surrounding the origins of the name and the company can be found here.

In 1945, five years after becoming an owner of the mail order maple products business with his purchase of the Black Sign Maple Syrup Company and the John Shelby label, Preston C. Cummings and Black Sign purchased the Vermont Maple Products Company. Buying out the South Royalton from Amos and Wendell Eaton, Cummings acquired the company name, their direct order mailing list, packaging equipment and supplies and their maple syrup inventory. The following year Black Sign changes its name to the Vermont Maple Products Company.

The company added Alfred W. Lane to its leadership in March 1947 ahead of plans for expanding the scale and sales of their operation. The following month the Cummings, Lane and R. Barton Sargent incorporated the Green Mountain Syrup Company occupying the same space as the Vermont Maple Products Company on Ayers Street in Barre. A year later, in February 1948, the Green Mountain Syrup Company formally changed its name to John Shelby, Inc. with Preston C. Cummings as president.

At some point in the late 1940s or around 1950 the Vermont Maple Products Company added exhibits to their plant, started offering tours, and began calling it the John Shelby Maple Museum. The name of John Shelby, The Maple Sugar Man was formally trademarked by the Vermont Maple Products Company in 1951.

Cummings further expanded the museum in the spring of 1952 with the addition of eight of painted murals created by Chelsea, Vermont artist Paul V. Winters. The murals depicted the evolution of the maple syrup industry from Native American sugaring to the colonial period and onto modern sugaring methods and equipment. The museum was popular and well promoted and was relatively unique at a time when few collections of maple sugaring antiques were on display elsewhere in Vermont.

Although the museum was a popular attraction it would appear that not everyone was pleased with how Mr. Cummings ran his business. In December of 1956 charges were filed in federal court against the Vermont Maple Products Company and Preston C. Cumming for violating the fair labor standards act. Specifically, Cummings was accused of paying employees under the then $1.00 legal minimum wage.

A few months later in March 1957 Cummings sold the Vermont Maple Products Company mail order operations, including the John Shelby name and museum, to Ezra R. Armstrong and Hal C. Miller, Jr. , both from Barre. Miller was an owner of the local Coca-Cola bottling company.

However, in selling the company, Cummings was not free of his legal troubles. It turns out that Cummings was also under investigation for tax fraud covering the years 1954, 1955 and 1956. Cummings was accused of filing false personal income tax returns and falsifying the taxable wages to employees he reported to the Internal Revenue Service. Cummings pled guilty in June 1960 on 16 counts and was sentenced to one year and a day in federal prison. Later the following year, Cummings appeared in a newspaper advertisement as the manager of the Barre branch of the Eastern Investment Corporation.

At some point around 1960 it appears that Miller and Armstrong sold the Vermont Maple Products Company and John Shelby Museum to Louis Hall, an associate of Miller with the Coca-Cola bottling company of Barre. As owner and full-time manager of the maple museum, Hall was engaged in the day-to-day operation of the mail order business and the tourist attraction, even serving as the president of the Vermont Attraction Association for a few years. In 1966 Hall sold the John Shelby Maple Museum to Rudolph “Shorty” Danforth and Clifford Eaton. A year later the museum building was purchased and razed to accommodate the expansion of what was then the neighboring Carle and Seaver tire shop.

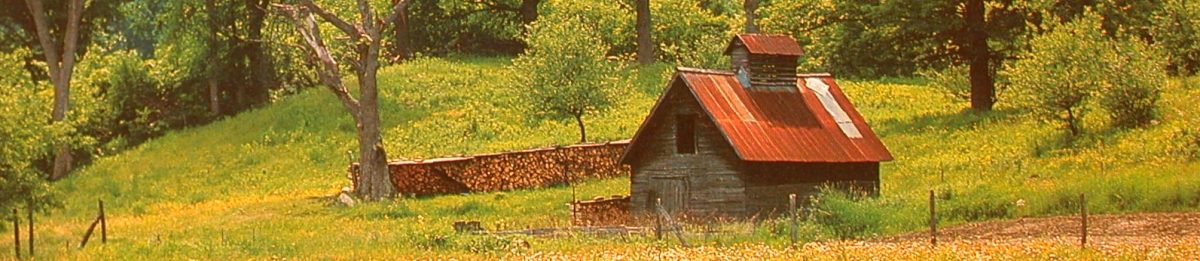

In 1966 Danforth and Eaton expanded their existing sugarhouse on State Route 14 in south Royalton to become a roadside maple themed restaurant called the House o’ Maple Vermont Sugar House. The artifacts and memorabilia from the purchase of the Shelby Maple Museum became a center piece and important attraction at the restaurant, bringing an end to the life of the fictitious John Shelby.

In 1975 Clifford Eaton bought out his partner Shorty Danforth’s portion of the restaurant business and in turn Danforth purchased Eaton’s share of the maple museum collection. Not long after, Shorty Danforth (who was a large man) sold the maple museum collection to Tom Olson of Rutland. Olson gave the collection a new home as the centerpiece of the New England Maple Museum which he built and opened in 1977 in Pittsford, Vermont. The museum is still open to this day preserving and sharing the collections, painted murals, and legacy of the mysterious Maple Sugar Man, John Shelby.