The Maple Syrup History website is pleased to share the following guest contributor post.

By Brenda Battel

The Battel family has produced maple syrup on its Michigan centennial farm since 1882. That’s when George Battel came from Ontario to settle 80 acres of land that he had purchased from a lumber company. The farm is located six miles northeast of Cass City, Tuscola County, MI.

In 1882, much of the land in Michigan’s “Thumb Area” was no longer of use to the lumber companies. The Great Fire of 1881 swept through Tuscola and surrounding counties in early September. More than a million acres burned. Hundreds died. Thousands were left destitute. It was the first official disaster that the American Red Cross responded to.

On the future site of the Battel farm, the fire spared a ten-acre grove of sugar maple and beech trees. This is where, six generations later, the family continues the tradition that George started in 1882.

Syrup in the early decades was produced for personal consumption. In the late 1920s, George’s sons (John, George and Daniel) started selling syrup commercially. It sold for $1 a gallon during the Great Depression of the 1930s. The brothers produced 75 to 100 gallons of syrup each spring.

Every generation since has carried on the tradition: the Arthur Battel family (third generation), the Mark Battel family (fourth generation), and the Bob Battel family (5th generation). That includes Bob’s daughters (sixth generation). There are currently three generations working together in the family business: Mark and his wife, Diane; son Bob; his daughters, Addy and Dori; and their mom, Sue.

Bob says he feels a connection to his ancestors every spring.

“You kind of relate with what they did,” Bob said. “Each spring you look forward to the season starting. I’m sure George did too — and John and Dan and Art… You kind of feel connected to the ancestors in the end of February and beginning of March.”

Not only has the current price increased from $1 to $54 per gallon, but production has doubled since the Battel brothers started selling syrup in the 1920s. This is due to technology and efficiency — which are welcome improvements considering the amount of manual labor the task of making syrup entailed in the past.

Technology also allows the farm to be a family operation. Because of tubing, reverse osmosis and an evaporator upgrade, the Battels do not need to hire anyone outside of the family.

“(Production) depends a lot on the weather during the season,” Mark said. Below freezing temperatures at night and warmer days allow for optimum sap flow.

He said that in the early years of the commercial operation, the entire woods didn’t always get tapped. A tree must be tapped in order to harvest sap. A small hole is drilled into the tree so that the sap can flow through a spile, which is placed inside the hole. For more than a century, buckets were hung from the spiles to collect sap.

Twenty years ago, the family invested in a tubing and pump system, which eliminated buckets. Tubes are connected to the spiles. Tubes carry the sap through the woods to a pump station, which creates a vacuum. The sap is pumped into a holding tank near the sugar shack, where it is boiled into syrup. The tubing/pump system allows the Battels to harvest sap from smaller trees. Production increased by a third when the tubes were added.

Prior to installing tubes, there were about 500 taps in the woods. Today, there are 700. The tubing/pump system didn’t just make it possible to tap more trees. It reduced a lot of labor spent gathering sap. Before the tubes were installed, Mark would drive a tractor and wagon through the trails in the woods. All 500 buckets of sap were manually dumped into the holding tank on the wagon.

Bob’s most vivid syrup-making memory is of his grandfather, Art, driving the tractor and wagon through trails in the woods to collect sap from the buckets hanging from the trees.

Seven years ago, the syrup operation, now known as Battel’s Sugarbush, LLC, invested in a reverse osmosis system.

“It takes some of the water out,” Mark said. “So it reduces your boiling time, and it uses less wood — less fuel.”

In 2020, the Battels upgraded the evaporator, which also makes the process more efficient and further reduces boiling time. The evaporator is 3 feet wide and 8 feet long. It preheats the sap. The fire is also hotter due to a fan beneath the evaporator. Another change is that thick steam no longer clouds the sugar shack. The steam goes from the enclosed evaporator directly up the chimney.

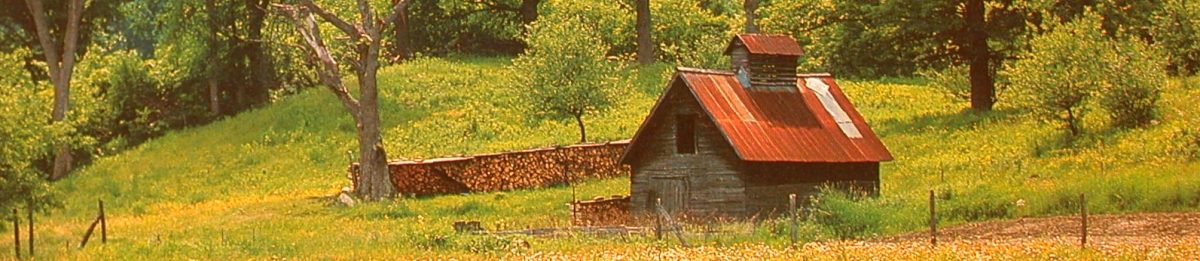

One thing hasn’t changed since 1882. It still takes 40 gallons of sap to boil down into one gallon of syrup. But it takes a lot less time today than it did for George 139 years ago. He used an iron kettle over an open fire. Near the very spot where George boiled his syrup sits the modern sugar shack. It houses the evaporator, reverse osmosis system, wood pile and canning station.

When Addy was 12, she won a grant to launch a new syrup business with neighbor and former business partner, Ethan Healy, who was 13. County Line Kids Pure Maple Syrup taps and gathers 100 of the taps on the farm. They boil, can, market and sell 10-15 gallons of syrup each spring. The kids use small, novelty containers for the finished product. The largest size is a pint. County Line Kids splits the profits with Mark, to pay for leasing the trees and using the facility to boil down and can the product.

Addy, now 18, is attending Michigan State University as a third-generation Spartan. Although Addy still helps in the woods, she passed the responsibility for managing County Line Kids to 15-year-old Dori.

“It gives me experience running a business,” Dori said.

She has been involved in managing the business for a couple of years. “I’ve been helping Addy from the start (of County Line Kids),” she said.

Dori is happy to carry on the tradition that George started in 1882. “It shows how committed everyone is,” she said.

Addy is a proud syrup maker as well.

“I’m proud to be the sixth generation in my family to make maple syrup,” Addy said. “Spending springs in the woods with my family watching the woods come to life is a pretty great legacy to be a part of.”

The sugar shack remains popular as ever with Battel kids like Asher, age 12 and Elias, age 11 (Bob’s sons). It is a spot for weenie roasts and family gatherings. The menu includes marshmallows and s’mores. The boys also help maintain the woodpile.

Bob continues the tradition because he enjoys it and it’s fulfilling. “It’s something to share with my kids,” he said.

The syrup season is short. It usually starts in early March, and lasts four to six weeks, depending on the weather. When the nights freeze and the day temperatures are above freezing, the trees are tapped. The season ends when the trees start to bud.

Other Battels involved in syrup making over the generations include: Annie (George’s wife), Bessie (John’s wife/Art’s mother), Lilian (Art’s sister), Marjory (Art’s wife), John (Art’s son) and Margaret (Art’s daughter).

Over the past 139 years, the tradition has required a lot of hard work, dedication and perseverance from six generations of Battels. Nevertheless, sweet memories abound and are cherished by them all.

—————–

Brenda Battel, Mark and Diane’s daughter, is a member of the fifth generation to grow up on the maple syrup farm alongside brother Bob. She is a writer who lives in Cass City, MI, not far from Battel’s Sugar Bush. She can be reached at brendabattel1@gmail.com.