As someone with a strong interest in the history and anthropological study of Native American resource and land use, in particularly maple sugaring, there is one particular photograph that has always interested me. I first saw this photo in Thomas Vennum, Jr.’s Wild Rice and the Ojibway People. Published by the Minnesota Historical Society in 1988, Vennum, then an anthropologist with the Smithsonian Institution’s Office of Folklife Programs, included the photo in a section of his book where he was describing the layout, activities and technology in use at the various Native American wild rice camps he visited across Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota.

The photo was taken on the Reservation of the Lac Vieux Desert Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians by Robert E. Ritzenthaler of the Milwaukee Public Museum during field work in the late summer of 1941. In the photo Joe Pete and his wife are shown parching wild rice in a large flat rectangular sheet metal pan over a wood fire. The pan looks to be about three feet by six feet in dimension with six inch deep sides, rolled rim at the top and two sets of handles on each side. As the caption in Vennum’s book notes “Joe Pete and his wife parching rice at Lac Vieux Desert, Wisconsin, 1941; the use of a rectangular metal trough and broom is unusual.” Instead, it was customary to use a kettle or kettle like metal washtub to parch rice. After harvesting wild rice by canoe from shallow lakes and rivers in the region, the rice was taken to nearby ricing camps or brought home to dry, parch, thresh, and winnow. Parching was historically carried out by heating and drying the rice grains in a large kettle over a fire, constantly stirring to avoid scorching or burning, such as shown in the photo below.

The novelty of using the unusual metal trough for parching rice is what caught Vennum’s eye in examining the photo. What he did not seem to realize at the time was that he was looking at a photo of Mr. and Mrs. Pete putting a maple sugaring flat pan to use as a wild rice parching kettle. While at first glance, it might seem an unusual departure from the traditional kettle or tub, it makes perfect sense and is actually a rather ingenious re-use of technology already on hand. Alongside collecting wild rice, making maple sugar and maple syrup, was and still is, one of the important seasonal gathering activities carried out every year in the Lac Vieux Desert community. Located on the north shore of Lac Vieux Desert in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, this Ojibwe community has occupied this village site for over two centuries. During that time tribal members established many maple sugaring camps throughout the maple woodlands surrounding the old village known as Katekitgon.

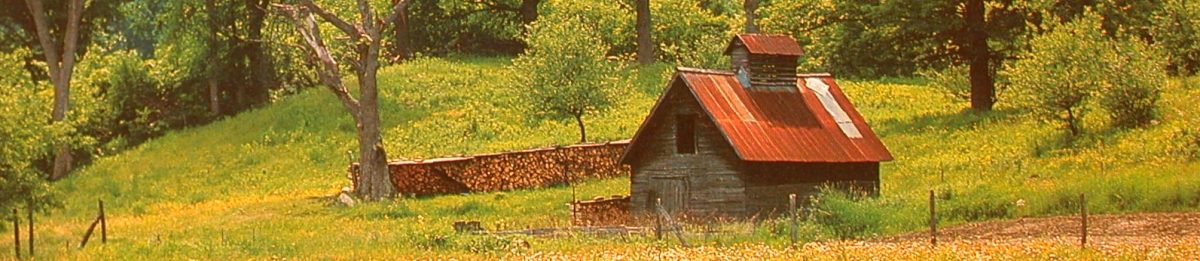

With Euro-American settlement, land cessions treaties, and other changes in land ownership, control of much of the Lac Vieux Desert territory was lost, with a great deal of the lands closest to the traditional village site becoming lands of the Ottawa National Forest. In 2001 I was working as an archaeological field technician for the Ottawa National Forest and was fortunate be tasked with conducting a re-survey of a large parcel of National Forest land adjacent to the lands of the old village in anticipation of a land exchange where these traditional lands would be returned to tribal ownership and control. Past archaeological surveys of the area had identified a wide variety of historic sites and activity areas associated with the village most notably dozens of maple sugaring sites. But in tromping through the woods, describing, mapping and photographing what I found, one particular site really got me excited. It was a sugaring camp like many others with a scatter of rusted, re-used metal food cans left behind from collecting sap at the maple trees and the nearly disintegrated remains of a stone and earthen bermed boiling arch.

What made this site different and gave me goose bumps that day was the appearance of a large rectangular metal trough with two sets of handles on each side. I knew that trough! That was the same trough that I had looked at so many times before used for parching wild rice in the photograph in Vennum’s book.

Well, at least it “looked” just like that trough and the Lac Vieux Desert context of both the trough in the photo and the maple sugaring flat pan found at the sugaring camp made it absolutely plausible and I would argue even probable that they were the very same pan. Making finds likes this and connecting what would seem like rather disparate dots are part the fun of archaeological and historical discovery. Moreover, this was a great reminder of the adaptability of people and the fact that sometimes there is more than what meets the eye and things are not always what they seem.