In searching for detailed descriptions of maple sugaring methods and equipment from specific periods of time in our past, one of the most interesting publications comes from a piece by C.T. Alvord titled The Manufacture of Maple Sugar. Alvord’s report appeared in the first Report of the Commissioner of Agriculture for 1862 which was published in 1863 by the Government Printing Office in Washington, D.C. This was the first official agricultural related report of the newly formed United States Department of Agriculture, which was organized by law in 1862.

C.T. Alvord was Calvin Thales Alvord (1821-1894) a lawyer, progressive farmer, and sugarmaker who lived his whole life in Wilmington, Vermont. Alvord was a regular contributor to the farming and agricultural journals of his time such as the Country Gentleman, American Cultivator and Rural New Yorker, providing insights and opinions on everything from growing grass seed, to raising lambs and prized short horns, and of course maple sugaring. In fact much of what he wrote for the Report of the Commissioner of Agriculture for 1862 was previously published by him in volume 15, number 19 of the Country Gentleman in 1860 under the title “Sugar Making in the Olden Time.”

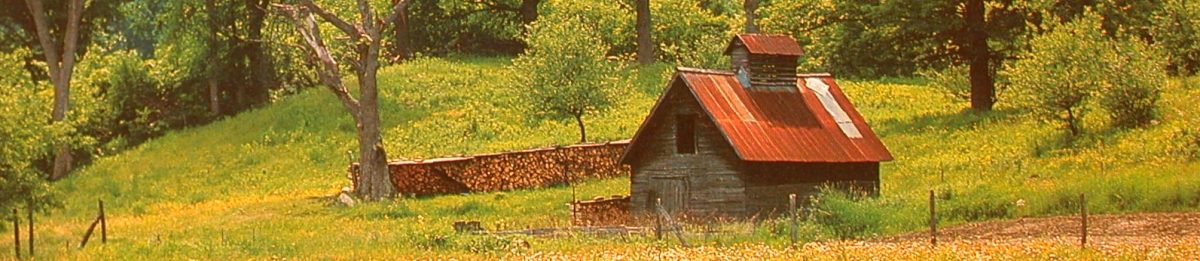

What is especially interesting about Alvord’s 1863 report is that he starts off with a description of what a typical sugaring operation was like about 25 years earlier, circa 1835, before bringing the reader up to date on what was the state of the art around 1860. Alvord’s description of sugaring in the early 1800s emphasized the use of multiple iron kettles for long nights of boiling, V-cuts and U-shaped wooden slat taps transitioning to tubular wooden spiles in drilled holes, and rough split log collection troughs transitioning to wooden pails on the ground or hung on spikes. The sugaring camp featured crude shacks in the woods for storage and shelter for the people when boiling but not for actually protecting the kettles or sap. Of course the product of those times was exclusively maple sugar.

Related to that, Alvord’s report is useful in showing how much maple syrup, or maple molasses as they sometimes called it, was being made by the early 1860s. It shows that the shift away from sugar production was well underway prior to the Civil War. In fact Alvord notes “…many farmers are now making ‘maple sirup’ to sell, instead of maple sugar. At present prices it is thought to be more profitable to make sirup than sugar.” It is interesting that he put the words “maple sirup” in quotation marks, when using that word choice instead of molasses as if it was a new word for the sugarmaker’s vocabulary. Alvord goes on to say that in recent years the maple sugarmakers in his area of Vermont have “to some extent” been making maple syrup instead of maple sugar and putting it up in wooden kegs and metal cans holding from one to four gallons.

Alvord’s 1860s description is important in that it shows how early much of the technology of the late 19th century was in use. With the exception of the flat pans on brick arches being replaced by evaporators with baffles and drop or raised flues as well as the shift to cast iron spiles and sheet metal collection pails, very little improvement was seen in the technology for the next 40 or so years. Even the sugarhouse described by Alvord was little changed in layout and form by the turn of the century.

Alvord even describes a kind of pipeline of grooved wooden slats laid end to end to direct sap from a gathering point higher in the sugarbush down to the sugarhouse. Recognizing the drawbacks of the open wooden pipeline for debris and snow and rain to affect the sap, Alvord notes that there were even examples of tubular tin “leading spouts” as he called them which was a “great improvement on the wooden spout. It can be used as well in stormy as in pleasant weather. It is made in the form of a tube or a pipe, in lengths of eight feet. The size of the tube generally made is one-half inch, and costs thirty-seven cents per rod; one end of these spouts is made a little larger than the other, so that the ends will fit tight in putting them up.” This description of a metal pipeline notably predates the invention and use of the better known Brower Gooseneck metal pipeline by a good 50 years.

A PDF of the entire report can be viewed and downloaded from the link above with the Alvord chapter found on pages 394 to 405.